Inside a Manic-Depressive Mind: The ways in which bpNichol’s chapbook “Lament” seeks to enter the mind of the late d.a.levy.

By Danielle (Cheryl) Wong

***Originally submitted 23 Octoober 2019 to Dr Jason Wiens, in part for credit, for ENGL 372: Canadian Literature at the University of Calgary***

***Not only is this essay subject to copyright, but any unauthorized use without citation is considered academic misconduct (plagiarism). You are welcome to consult this paper if you provide the appropriate citation(s)***

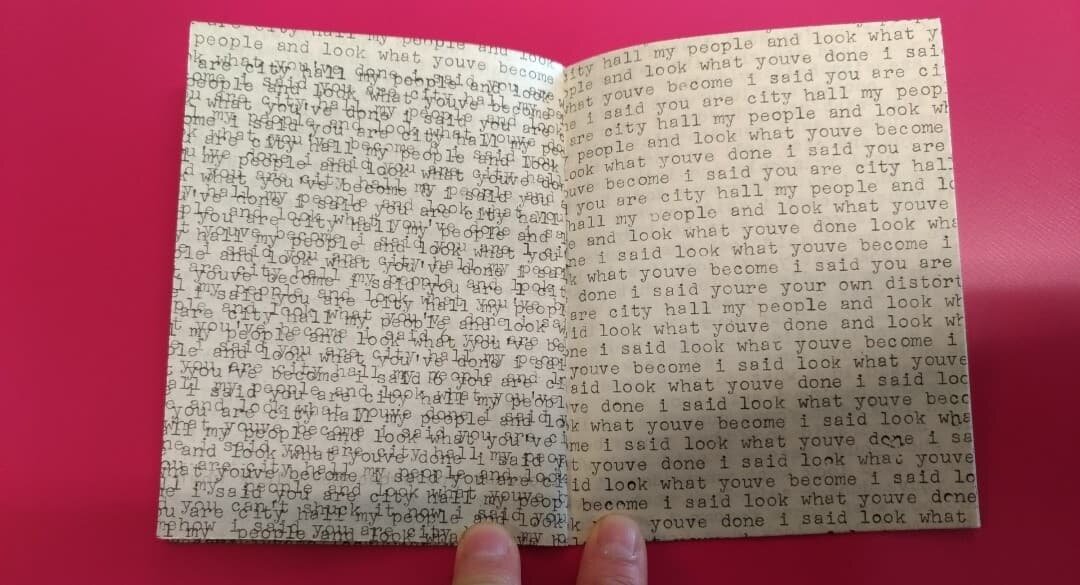

bpNichol’s chapbooks explore a rich variety of perspectives through both visual effects and the text itself. In his 1969 chapbook titled “Lament,” bpNichol enters the mind of the late poet and artist d.a.levy at a moment likely near the time of his suicide in 1968 (Kuhar). bpNichol uses the visual layering of text upon small, thin pages to show three distinct phases of manic and depressive moments within d.a.levy’s mind. The text itself reflects the dedication bpNichol makes on the cover, which further enhances the reader’s understanding of the speaker’s thoughts. “Lament” is a powerful poem that exemplifies the complexity of the human mind through a variety of aesthetic techniques.

In order to fully appreciate bpNichol’s chapbooks, we must remember that they are small press publications and thus are often crafted with a sense of artistry unlike that of conventional books. In the case of “Lament,” which was originally performed in 1969 as part of a reading at the University of British Columbia prior to its publication later in the same year (bpNichol n.pag)[1], bpNichol has attempted to render a sound poem into a paper form. The paper copy has then been rendered digitally for the purposes of this paper. We must remember that the first rendering from oral to written forms had likely presented some challenges to bpNichol, but those will not be discussed further in this paper. Rather, we will focus on the difficulties in rendering a small chapbook dependent on its visual effects into a digital form. The size of the book is difficult to truly comprehend in a digital image. A variety of items could have been placed for scale alongside the chapbook in the image, but this would still not allow the viewer to experience the tactile and visual significance of the chapbook’s small size. The chapbook fits in the palm of the hand, which allows it to represent a small window into the mind of d.a.levy. bpNichol uses the size of the book to demonstrate that he wants the reader to consider this a snapshot of the mind, rather than a holistic image of it. He wishes to show an episode, likely near the death of d.a.levy, so that the reader can carefully consider the potential mindset of the poet in his final moments. The pages are made of thin, slightly yellowed paper, which allow the words to be visible through them. This is done to show the blurring of the thoughts and how each does not exist as a discreet object, but rather as an interconnected web of repeated ideas following a mental journey from mania to depression, then back to mania. The thin pages also provide a delicacy to the piece, bringing a fragility to the mental state of d.a.levy and demonstrating the fleeting nature of thoughts and life itself. The translucency of the pages is difficult to show digitally, as the words become hard to read as they are mixed with the words on the opposing side of the page. Also, the lack of page numbers makes it easy to lose one’s place in the chapbook when rendered digitally, which would further contribute to the confusion caused by including images of the translucency of the pages. For these reasons, pictures of the chapbook have been taken with the pages pressed against each other so that light does not pass through them. Due to the especially strong visual nature of bpNichol’s “Lament,” a medley of difficulties arose in the process of rendering it in a digital form. Some solutions have been implemented, but there is no replacement for the experience a reader gets when they get the opportunity to read the book in its physical form.

On the cover of “Lament,” bpNichol dedicates the chapbook to “the memory of d.a.levy who took his own life.” It then becomes important for us to consider the life of d.a.levy in order to better understand this poem. bpNichol’s inclusion of “who took his own life” places a large emphasis on the death of d.a.levy. This mention becomes significant when we consider the artistic life of the late poet. d.a.levy was a man from Cleveland, Ohio whose artistic career began after his discharge from the military due to disobedience attributed to manic-depressive tendencies (Kuhar). bpNichol addresses d.a.levy’s manic-depressive tendencies in the field composition of the text. The repetition of the same lines throughout the chapbook encourages readers to almost ignore the text itself and consider the visual effect of the layering of text as a message in itself. Upon release from jail after being arrested for his artwork and poetry, d.a.levy became paranoid of recapture and eventually committed suicide in what his close friend and fellow publisher Robert J. Sigmund- also known as rjs- believed was a manic high (Kuhar). To reflect this, bpNichol has shown a clear journey from mania to depression that culminates in a repeat of mania. This can be seen in the field composition of the chapbook. The more spaced out pages depict mania while densely packed text shows a depressive episode. It is important to note that the pages do not jump from spaced out to dense immediately, but rather slowly increase, then decrease, in density. This is so bpNichol can show that d.a.levy’s mind did not switch suddenly between states, but rather moved quickly between states. Mental state is shown to be continuous rather than discrete.

d.a.levy’s visual art and poetry both sought to address social issues in the 1960s and eventually landed him in jail (Kuhar). The text itself in “Lament” shows how the speaker feels betrayed by the city itself. As d.a.levy’s artwork and poetry focused heavily on images of Cleveland (Kuhar), it can be seen in “Lament” that bpNichol proposes the lack of public attention on d.a.levy’s poetry was a contributing factor in his suicide. bpNichol writes,

“that you've done i said you are city hall my people and look what you've become

i said you are city hall my people

come i said you're your own fuzz no

you're your own distortions and

what you've done 9 i said you

[b]ecome i said you're your own govern[ment]

[you]'re your own people you gotta make i[t]”

It is important to note that these lines run one after another in the chapbook and thus have been parsed in a way that creates logical phrases for the sake of clarity. The lack of capitalization in the chapbook reflects the pen name d.a.levy went by. The use of only lowercase letters indicates a lack of prestige, as shown by a lack of formal title, that reflects the lower economic status of the late poet. It also follows the lack of capitalization that d.a.levy used for his own name. The first two cited lines address the speaker’s fellow citizens and equates them to the government. This is likely due to the democratic nature of the United States of America, in which it is believed that the wishes of the people heavily influence the government’s actions. Thus, bpNichol is proposing that the people are the ones who created the society that betrayed d.a.levy. The next two lines are also related; they go into further detail about the real identities of the people. They are classified as their “own fuzz” and their “own distortions.” The fuzz is slang for the police. bpNichol uses this term to show how the people are responsible for policing themselves and each other, which also creates an atmosphere of suspicion and mistrust. This contributes to bpNichol’s message of d.a.levy’s feelings of mistrust towards those in his city. It also reflects his paranoia of being caught by federal agents (Kuhar) because it shows the speaker feeling as though the police are constantly surrounding him and watching him. The idea of the people of Cleveland as their own distortions lends itself to an understanding of the chapbook showing the jumbled nature of d.a.levy’s thoughts in both his manic and depressive modes. The speaker labels others as distortions, indicating their distance from reality and the warped nature of their intentions and personalities. The fifth line indicates a further chaotic jumbling of the speaker’s thoughts and also lays the blame on the people of Cleveland for all of the trespasses d.a.levy may have believed were committed against him. The number in the middle of the line changes as the poem progresses in a seemingly random sequence, which adds to the confused nature of the speaker’s thoughts. The final two lines reflect the poetry and artwork of d.a.levy. They call for the people to own their decisions, lives, and society. It is a cry for the citizens to shape society rather than sitting idle and letting themselves be swept along by the current of “oppressive conservatism” (Kuhar) and the “heavy hand of authority” (Kuhar). An examination of the repeated text in the chapbook allows readers a glance into the manic-depressive mind of the late d.a.levy, as told by bpNichol.

“Lament” makes inventive use of both visual effects and textual references to bring readers into the shifting mindset of the late poet and artist d.a.levy. bpNichol uses the physical pages and size of the book to initiate the idea that the chapbook is a sort of mental snapshot of d.a.levy’s mind. He then implements effective use of field of composition to recreate the manic and depressive episodes d.a.levy was prone to. Finally, the text of the chapbook serves to reinforce the reader’s understanding of d.a.levy’s thoughts about his city and his people. bpNichol’s “Lament” is a striking example of his small press publications seeking to provide its readers with a unique perspective on life.

Works Cited

bpNichol. Lament. Ganglia Press, 1969.

Kuhar, Mark S. “50 years after d.a. levy’s death, the legend of Cleveland’s visionary poet and provocateur lives on.” Cleveland.com. 14 Nov. 2018, www.cleveland.com/entertainment/2018/11/50-years-after-da-levys-death-the-legend-of-clevelands-visionary-poet-and-provocateur-lives-on.html. Accessed October 18, 2